One Step Closer: The Mystery of The 73 Year Old Somerton Man

June 4, 2021

In the early winter of 1948, a man’s body was discovered propped up against a seawall on Somerton beach in southern Australia. He was wearing a brown suit and a half-smoked cigar resting on his collar. He developed the nickname, Somerton man. The case itself is known as the Tamam Shud case or more commonly, the Mystery of the Somerton man. The real mystery, however, is who was this man and what happened to him? After 70 years, we might be one step closer to solving this case.

Professor Derek Abbott of University of Adelaide first heard the story of the Somerton man in 1995 and had spent many years campaigning to have the body exhumed by scientists in order to determine his identity.

This plan was finally set in motion last month in West Terrace Cemetery, where the body of the Somerton man was buried under a headstone marking “the unknown man.”

According to CNN, South Australia Police Detective Superintendent Des Bray had told reporters that the exhumation was “much more” than just “closing the file on one of Australia’s most intriguing cases.”

“There are people we know that live in Adelaide…they deserve to have a definitive answer” he told reporters.

According to CNN, when the body was examined, more questions were raised than answers. The cause of his death was not natural, there were no signs of violence, all of the labels on his clothing had been cut off and he did not carry an ID.

The Somerton man was in his mid 40’s or 50’s, 5 ’11, had grey-blue eyes and gingery-brown hair that was greying at the edges. Pathologist John Cleland noted that many people who are on their way to the morgue have disgusting toenails, whereas this man’s toenails were clean.

Paul Lawson, a taxidermist, noted that his calves were “particularly pronounced.” This evidence leads many to believe that he might have been a dancer among other things such as a blackmarket trader, a sailor or even a spy.

Cleland inquired that he might’ve been European. “I would say he looked very much like a Britisher,” he says. “His hair was brushed back from the forward, and there was no part in it.”

One tailor’s examination of the man’s coat begged to differ. “He had either been in America or bought the clothes off someone who had been there,” said Detective Raymond Leane on behalf of the tailor. “Such clothes are not imported.”

While there were many clues found during the examination, all of them lead to dead ends.

Multiple tickets were discovered; one suggested he took a train to Adelaide Railway Station from an unknown location, and another train ticket to Henley beach that was never used. Police discovered that the same orange thread that had been used to repair his trousers had also been found on his suitcase.

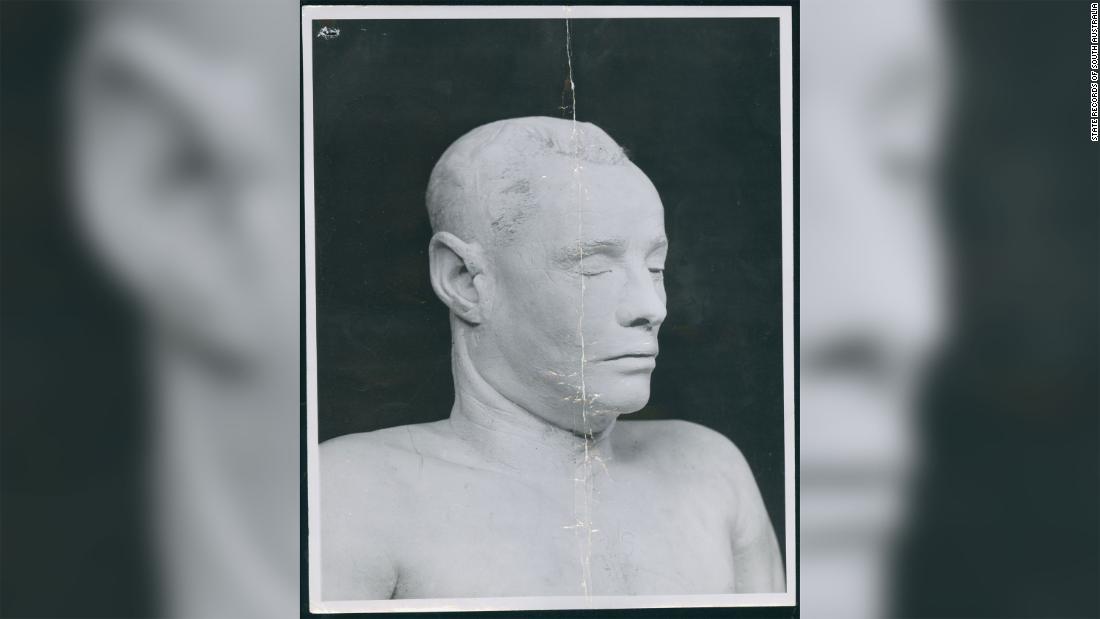

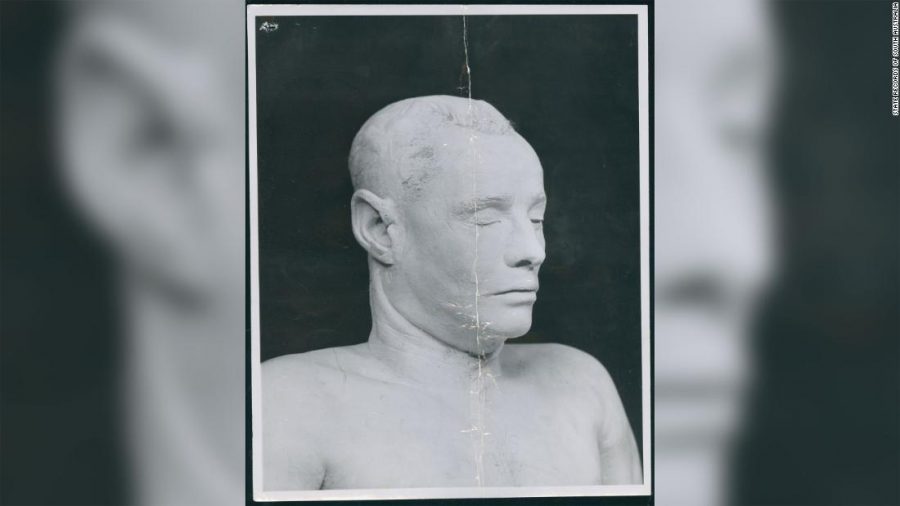

His body was embalmed so that police could be given more time to examine him. They also made a plaster case–aka death mask–as a physical reminder of who he was. The body was released for burial in June, 1949.

Finally in April of this year, there was a new piece of evidence.

Cleland had reexamined his body and found a hidden pocket with a piece of paper rolled up inside it that read “Tamam Shud” which means “the end” or “finished” when translated from Persian.

These are the last words to a poem called “The Rubaiyat” written by Omar Khayyam. They were torn from a book and given to the police. An unnamed man said he found it in his car the day before the Somerton man’s death. He did not provide further information after that.

Cleland said that the words supported his first conclusion that the man had taken poison. “I think the words were put there deliberately and indicated that intention that he was fed up with things,” Cleland told the inquest.

The book also contained two major clues inside.

One of these clues was a handwritten phone number. The number traced back to a woman who lived in the nearby Adelaide auburn of Glenelg. She denied knowing the man and was “horrified” when shown the death mask.

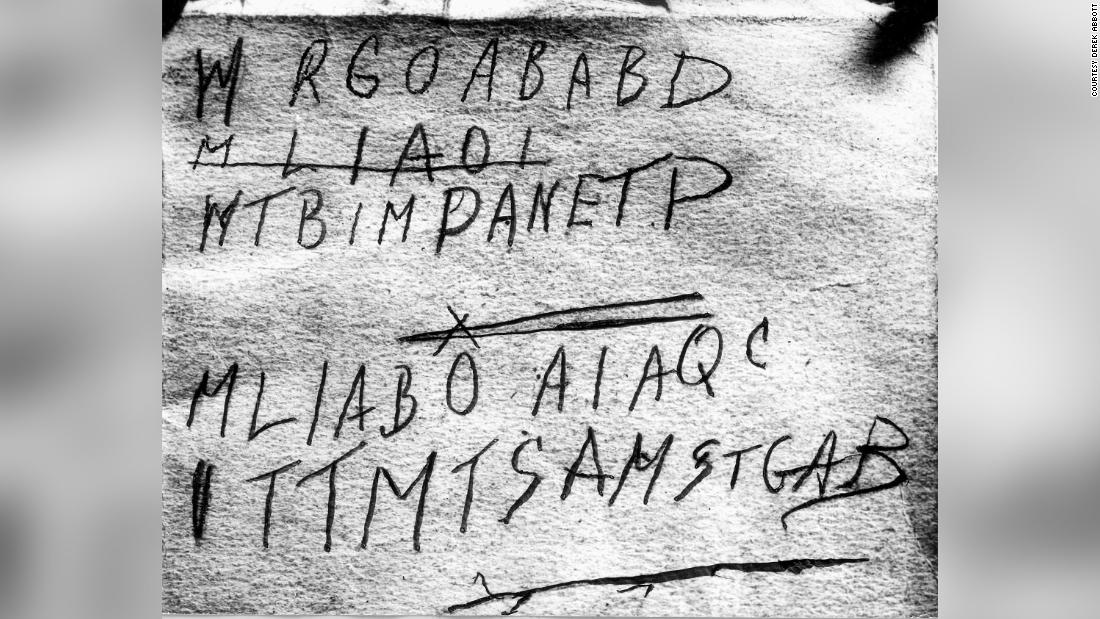

Next to the phone number was a scribbled code of letters that was thought to be a secret wartime code. When Professor Abbott and his students examined the code, they concluded that it did not have the sophistication that a wartime code usually has.

When Abbott retraced the phone number, the woman who had previously owned it had passed away. He then tracked down the woman’s son, Robin Thompson, who was also deceased. He then looked for any relatives and found Rachel Egan, the daughter of Robin Thompson.

Abbott theorized that the Somerton man was Egan’s father. But when Egan’s DNA was tested with strands of hair found in the plaster, there wasn’t a match.

DNA testing was used primarily in the 1980’s which was a few decades after the Somerton man’s death. Director of Forensic Science SA Linzi WIlson-Wilde is optimistic of the DNA testing now. “We’ve gone from requiring quite a considerable amount of biological material, a sizable quantity, to being able to get a result from an amount of DNA that you can’t even see with the naked eye,” she said.

Abbott says that similar cases that have been solved in America have taken time, however, he’s prepared for a two-year haul “if that’s what it takes.”

If there is a match to the Somerton man, detectives will attempt to find his living descendants.

Ms McCarthy • Jun 4, 2021 at 11:43 am

Great article! I never heard this story before and am now intrigued. Please do a follow-up if more information comes to light.