My newest obsession is the HBO Max series The Gilded Age. Set in the Gilded Age of New York City (between the end of the Civil War and the turn of the 20th century), new and old money battle for the top spot in high society. A big topic in the show is the position of women in a male-dominated society. One topic that struck me the most occurred in episode five of the second season, titled “Close Enough to Touch.” We are introduced to the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge, now one of the world’s most recognizable bridges and the first to use steel as its cable wires. In the show, a main character’s son, Larry Russell, is sent to Washington Roebling’s, an engineer, residence to oversee the final plans for the Brooklyn Bridge. He later finds that Roebling has fallen ill, leaving him incapable of completing the bridge. Roebling’s role as chief engineer had silently been passed on to his wife, Emily Warren Roebling. Emily was responsible for most of the construction process on the Brooklyn Bridge. Unfortunately, her ailing husband’s name took all of the credit for the bridge. I’m here to tell you of Emily Roebling, the mastermind, and the secret engineer, behind the Brooklyn Bridge.

Emily Warren was born in 1843 to Sylvanus and Phoebe Warren. She was educated at Georgetown Academy in Washington D.C. where she studied everything from French to astronomy, to mathematics. She was knowledgeable in nearly all subjects, including the skills of a good housewife. Warren met her husband towards the end of the Civil War when Washington Roebling served as an engineer for the Union. They were married in 1865 and shared one son. In 1867, the Roeblings went over to Europe so that they could help Washington Roebling’s father, John A. Roebling, with his plans to construct the Brooklyn Bridge, a suspension bridge consisting of caissons and steel cables. Some background knowledge: caissons are impermeable tubes that are built well beneath the surface of a body of water, which is later filled with concrete for stability. Before they are filled with concrete, engineers and construction workers can safely work without the total pressure of the water around them. The caissons of the Brooklyn Bridge are 44 feet below the surface, resulting in a water pressure of 19.5 pounds for every square inch.

Unfortunately, chief engineer John A. Roebling never got to see his masterpiece constructed. In 1869, his foot was crushed by a ferry that collided with the dock. After he had two toes amputated, he died from complications of tetanus. Washington Roebling became chief engineer and the construction of the bridge would be overseen by him. The historic build began in January of 1870, but more tragedy was to follow. Despite sounding marvelous, building the bridge was no easy task. At least 20 people were killed, and many more suffered from decompression sickness; caused by a rapid increase or decrease in the pressure around you. In 1872, Washington caught decompression sickness. He came out of a caisson too quickly, causing him to pass out. This was only the beginning of his suffering. He was left partially paralyzed, partially blind and deaf, and partially mute for the rest of his life. Washington was bedridden. This, however, did not stop the building of the Brooklyn Bridge.

Emily stepped up. She quickly learned the mathematics and science behind the construction. She ended up writing all of her husband’s letters regarding the construction of the bridge and reading all of his notebooks. She would go back and forth from the construction site to her house, taking notes, and controlling the build-up of the bridge. She spoke with workers, communicated with contractors, and did all the work that her husband would do if he was capable. Many contractors were puzzled by Emily’s appearance at some of the meetings, but they were wowed by her knowledge of engineering and didn’t object. The form of Emily’s work was unheard of during the Gilded Age of America. A woman, engineering a whole bridge? Emily had to keep a low profile, but this was hard, considering she was running the whole project. Rumors spiraled around society, theorizing that Washington was mentally unable to finish the bridge. This put her husband in danger of losing his position as chief engineer, which would leave him with no control over the project. Emily insisted that her husband was overseeing everything. She told no lie, but hid the real truth: Washington was overseeing everything, just from his bedroom with a pair of binoculars. Nevertheless, she completed the ever-famous Brooklyn Bridge.

In 1883, Emily’s work was done, and the Brooklyn Bridge was open to the public. The opening ceremony was a huge event. People lined up their carriages along Brooklyn Heights, and every neighborhood surrounding it. People dined on top of buildings, on the streets, and in their carriages to see the grand opening of the Bridge that would connect Brooklyn and Manhattan. Emily was the first person to ever cross the bridge, carrying a rooster under her arm for good luck. During the ceremony, many people thanked Washington for his contribution to New York City, but Congressman Abram Stevens Hewitt was the only one to thank Emily for her hard work and dedication directly. Hewitt honored her that night by saying that the bridge “[was] an everlasting monument to the sacrificing devotion of a woman and of her capacity for that higher education from which she has been too long disbarred.”* Even after Hewitt’s remark, she knew that her husband would get all the credit, but Washington never failed to praise her for her contribution to the construction of the bridge.

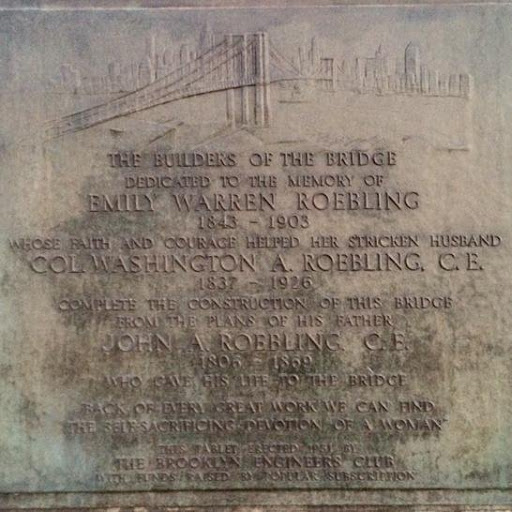

Emily Roebling is one of America’s first female engineers. She died in February 1903 due to stomach cancer. Today, there is a plaque on the Brooklyn Bridge that honors John A., Washington, and Emily Roebling, saying, “Back of every great work we can find the self-sacrificing devotion of a woman.” Emily is a role model to many women, and her work on the completion of the Brooklyn Bridge will not be overlooked.

* Quote courtesy of: schools.nyc.org

madeline • Apr 4, 2024 at 8:22 am

Love the article, Shan! 🙂 <3

Shannon Raneri • Apr 4, 2024 at 8:23 am

Thank you for reading!

csummacc • Mar 23, 2024 at 10:59 am

Shannon,

Great article. I was so impressed with Emily and her knowledge and how she was able to

achieve the things she did! A valiant woman – indeed!

Shannon Raneri • Mar 24, 2024 at 12:47 pm

I agree, she was extremely ahead of her time.

Chele Berner • Mar 22, 2024 at 8:38 am

Shannon, as soon as I saw the title of the article I thought of the Gilded Age. Once again, your article was informative and held my attention. Well done!

Shannon Raneri • Mar 22, 2024 at 9:12 am

Thank you! I cannot wait for the third season!